Film Criticism Workshop

Rediscovering Space

The Still Side (El Lado Quieto) by Miko Revereza and Carolina Fusilier

Slow and contemplative cinema is difficult to achieve and even more difficult to master. With The Still Side, directors Carolina Fusilier and Miko Reveresa utilize this meditative and observational mode to explore the remnants of an abandoned resort in Mexico. But what the camera finds among the empty disco halls, barren hotel rooms, and corroding concrete is more than just a passive record of a curious local spot left to time. The film explores the potential for the observational gaze to rediscover space—and, to a large extent, sound—a statement of cinema’s power to embed meaning in what seems like otherwise trivial observations of still life.

The film begins as the camera is swept along by ocean swells before it lands on the Capaluco resort’s rocky shoreline. The camera begins by looking at stationary shots of crevices in the rocks, pools of water, setting a rhythm for the rest of the film’s visual language. The sound of waves lapping up against the rock formations and the deep echoes inside oceanside caverns punctuate the soundscape. Almost barely noticeable on screen is the brief appearance of a curious shadow of a tentacle-like appendage swaying slowly against some rocks.

As the camera moves deeper into the resort the film intersperses a conversation between the directors, who suggest a creature, the siyokoy, who has been swept up in the ocean currents from the Philippines, now wanders in awe of these structures left by humans. Is this the mysterious shadow on the beach? Is what we see in the film from the point of view of the creature?

This extra layer of “fiction” seeps into the rest of the film as the camera continues to slowly and quietly observes the resort’s interior. Fiction and reality begin to blur and what we see can no longer be taken at face value. Shots of the architecture take on an otherworldly appeal, the ambient soundscape becomes more unsettling, the empty buildings seem post-apocalyptic.

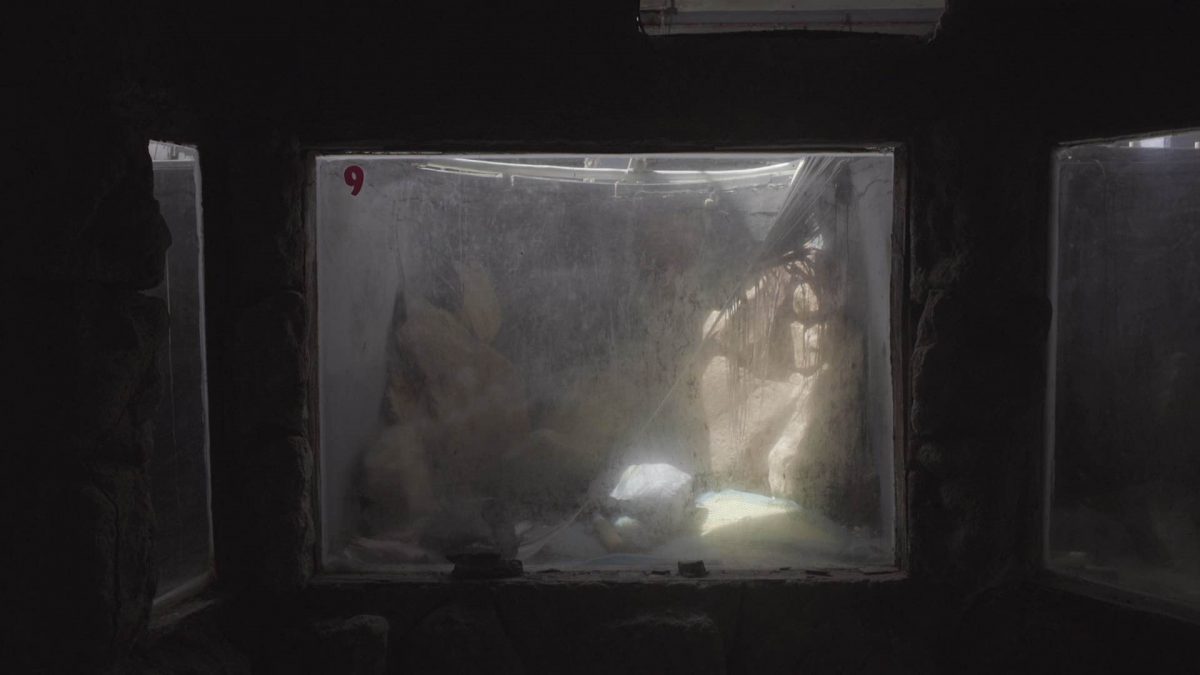

But the film does not wander too far off in this territory and the directors even pose this narrative in hypothetical terms. The Still Side still remains close to reality, a reality where the abandoned resort certainly does exist. The deeper we are taken into the uninhabited structures the more it becomes clear that the framing of this abandoned town is not for mere visual pleasure but to reflect on the real-world impact and implications of these decaying sites. When the camera is fixed on the wreckage of boats, the empty animal cages, and the corroding materials that have become ornaments of marine life around the resort, we are invited—through the slow-moving camera work—to think deeply about the effects of rapid development and the imprint of consumer culture on the environment. By thinking through landscape—one thinks of the discourse on landscape in Japanese avant-garde cinema—The Still Side presents a subtle yet effective mode of questioning societal ills, one that obscures spectacle in favor of contemplative long takes on seemingly insignificant views of the resort.

But the camera does not frame the area as all rot and decay. One of the most important rediscoveries of the film is how the abandoned resort is still full of beauty and life. The once gaudy disco, the scribbled graffiti, the chipped paint on the doodles on the wall, the mold growing on statues—there is something aesthetically pleasing in capturing these objects left behind, in reframing them with the camera in this new context as they stand as testaments to the past. While the exotic animals in the zoo and aquarium have been replaced by an overgrowth of nature, the filmmakers find the spaces repurposed and effectively reframed by new fauna: stray cats, ants marching, and bursting with life in the sea. The ambient sounds that haunt the resort, which achieve a sizable resonance when paired with the film’s still images, are in themselves a work of art, otherwise unnoticed traces of the past and the present that the filmmakers have unearthed from the ruins.

While the slow and contemplative mode of cinema may not be for everyone, The Still Side reimagines and rediscovers the contours of a forgotten site while providing viewers an intimate and unhurried engagement with cinematic space.

Christopher M. Cabrera